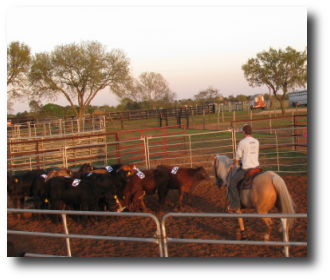

Last night we went out to Cryin’ Coyote Ranch for team sorting practice and chased some cows.

At no point in my entire riding history (or life) would I have ever imagined that this is something I would one day do.

There are cows, numbered 0–9, in two small round pens that are connected with a pretty wide  opening between them. The cows are all herded into one of the round pens, and two riders are in the empty one. As the first rider enters the pen with the cows, a number is called out, say “5”. The rider must separate cow #5 from the herd and put him in the empty pen. Her partner guards the opening to ensure that only cow #5 goes in there, and that he doesn’t come back out. Then the riders switch off cutting and guarding the cows in order — in this case, #6, 7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 — until all the cows are in the second pen, or until time runs out. You only have a minute to achieve this.

opening between them. The cows are all herded into one of the round pens, and two riders are in the empty one. As the first rider enters the pen with the cows, a number is called out, say “5”. The rider must separate cow #5 from the herd and put him in the empty pen. Her partner guards the opening to ensure that only cow #5 goes in there, and that he doesn’t come back out. Then the riders switch off cutting and guarding the cows in order — in this case, #6, 7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 — until all the cows are in the second pen, or until time runs out. You only have a minute to achieve this.

In none of my five or so turns did my partner and I get all the cows; I think our record was four of them. The major achievement of the first turn was not getting bucked off by Dunnie, who despite being a finished reined cow horse, gets so excited about the cows that he doesn’t know what to do with himself, gets frustrated by it, and then prances and jumps around while the cows ignore him. The second time around, I was able to get him to go after the cows, but we spent the entire minute chasing cow #5 while he ran us in circles around the ring ensconced in the security of his herd (at times with his head literally under the back legs of the cow in front of him) and I laughed my head off. But the third time! Let me tell you, getting that first cow in the pen was a thrill. I imagine it’s what hockey players feel like when they score their first NHL goal.

In none of my five or so turns did my partner and I get all the cows; I think our record was four of them. The major achievement of the first turn was not getting bucked off by Dunnie, who despite being a finished reined cow horse, gets so excited about the cows that he doesn’t know what to do with himself, gets frustrated by it, and then prances and jumps around while the cows ignore him. The second time around, I was able to get him to go after the cows, but we spent the entire minute chasing cow #5 while he ran us in circles around the ring ensconced in the security of his herd (at times with his head literally under the back legs of the cow in front of him) and I laughed my head off. But the third time! Let me tell you, getting that first cow in the pen was a thrill. I imagine it’s what hockey players feel like when they score their first NHL goal.

After that, I realized that making Dunnie wait in the line for our turn was ratcheting him up, and that if I cantered him around the warm-up ring in between, it’d give him something to think about and he’d cool himself off. I also had him doing spins, and with his elevated energy levels, we did some of the best ones we’ve ever done.

Our next couple turns after that were much more productive. Every time I either got a cow in the other pen or successfully blocked one that wasn’t supposed to come in I felt like pumping my fist in the air and cheering (I mostly restrained myself, but I’m told my face was lit up like the sun).

So the upshot is, now I’m addicted to this. Once he gets past the silliness, Dunnie is actually a pro. And as I’m gaining confidence, I can be more aggressive chasing those cows down. It’s quite exhilarating to ride right into a herd of cows and then be able to control them. It makes me feel pretty powerful to be able to push around cows, even though they’re little cows. The level of partnership and communication between horse and rider required for this is more than anything I’ve ever experienced. It means moving together as one toward the same purpose. As always, the tangible is more compelling to me than the abstract. I can certainly get behind working hard to get good at doing stuff in the ring and then winning competitions. But this is about as far from abstract as you can get. Horses are real. Cows are real. They are both big, and very vividly alive underneath and surrounding me.

The more I delve into all the different disciplines of riding, the more I see how there are so many ways to challenge myself and my horse. It’s like when I was taking English lessons, I saw some shiny stuff on the ground — and then when I started riding Western, I dug into this mother lode of possibility, where the deeper I dig, the richer it becomes.